How Warren Buffett’s Investment Style Evolved Over Time

A 25-year evolution where Buffett moved away from Graham's quantitive investment approach to Charlie Munger's qualitative business analysis approach.

In the investment world, few transformations are as fascinating as Warren Buffett's journey from hunting bargain-basement stocks in the 1950s to acquiring high-quality compounding businesses by the late 1970s. This shift wasn't sudden - it represented a 25-year evolution where Buffett gradually moved from Benjamin Graham's quantitative approach to Charlie Munger's qualitative business analysis.

Understanding this transformation in Warren Buffett's portfolio strategy can help modern investors avoid years of costly mistakes.

Stage One: The Net-Net Playbook (1950–1969)

The early years of Warren Buffett's investing career centered on the "cigar-butt" approach: buying companies trading below their working capital liquidation value, extracting the last bit of profit, and moving on. Graham's influential work taught that these statistical bargains outperformed because their rock-bottom prices provided downside protection.

Tool kit: Manual analysis, personal visits, balance-sheet focus.

Target companies: Undervalued industrials, transportation firms, resource companies.

Competitive advantage: Willingness to dig deep; Buffett personally investigated Midwest companies.

The strategy delivered results numerically. For instance, Cleveland Worsted increased dividends while trading at a discount to book value, then liquidated profitably. However, problems emerged in the Warren Buffett stocks approach.

This quote from Buffett's 1989 letter reflects his later perspective. Holding mediocre businesses rarely allowed compound growth; new problems constantly surfaced.

What Went Right

Downside Protection: 60% discounts to asset value provided safety margins.

Size Advantage: Small partnership size made micro-cap profits meaningful.

Value Realization: Corporate actions often unlocked value quickly.

What Went Wrong

Capital Recycling: Profits needed constant reinvestment—inefficient and costly.

Growth Limitations: As Warren Buffett's portfolio grew to $26m, bargains became scarce.

Industry Decline: Many targets were in sunset industries facing increasing competition.

Catalysts for Change

Charlie Munger's Influence (1959 onwards): Warren Buffett's partner Munger revolutionized their investment approach by demonstrating that paying fair value for exceptional businesses ultimately outperforms buying mediocre companies at deep discounts, as compound growth overcomes initial pricing considerations.

Learning from Disney & American Express: Warren Buffett's portfolio decisions with Disney and Amex proved instructive. While a 55% gain on Disney in one year seemed impressive, watching the stake multiply 2,000 times over subsequent decades was sobering. Similarly, selling American Express after it quadrupled turned out to be premature given its long-term trajectory.

Operational Challenges: The Berkshire Hathaway textile business, though acquired cheaply, became a management burden that never generated reinvestable cash flow. This experience convinced Buffett that mediocre businesses constantly consume capital without creating value.

Tax Considerations: Frequent trading of cigar-butt stocks triggered short-term capital gains, while holding quality compounders allowed tax-deferred growth with IRS effectively funding part of the appreciation.

Stage Two: The Moat Strategy (1972–Present)

The watershed moment came in 1972 when Warren Buffett's portfolio added See's Candies for $25 million, roughly 3 times tangible book value. Within 5 years, See's generated pre-tax earnings equal to the purchase price while requiring minimal additional capital. Buffett described this as "buying a stream rather than a pond."

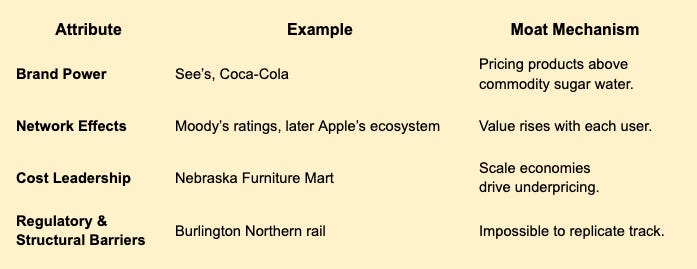

The new investment framework centered on durable competitive advantages, or moats - a term Buffett popularized that authors like Pat Dorsey later systematized.

A strong moat enables sustained high returns on capital and reinvestment at those rates, driving long-term compounding.

Key Characteristics of the Moat Era

Buffett's 1989 Berkshire letter crystallized the philosophy: "It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price."

Comparative Economics

A thought experiment illustrates the math:

Cigar-butt approach: Buy at $0.50 on the dollar, sell at $1.00 after two years. Pre-tax CAGR ~41%, post-tax ~30% (assuming 25% rate).

Moat path: Warren Buffett's portfolio strategy evolved to focus on buying quality businesses at reasonable valuations, aiming to compound at 20% annually over 20 years without selling. This approach, despite similar pre-tax returns, creates 20 times more wealth than the cigar-butt method after considering tax efficiency.

Common Misconceptions

"Moats = Overpaying." Warren Buffett's acquisition of See's Candies appeared expensive on book value metrics but was actually cheap considering its cash yield. His disciplined approach remained intact - he only paid premium prices when incremental returns were clearly visible.

"Moats Are Static." In managing his portfolio, Buffett vigilantly monitors moat deterioration (exemplified by his IBM exit). He understands that a competitive advantage isn't truly sustainable if it can't withstand technological disruption or regulatory changes.

"Net-Nets Are Dead." This strategy remains viable for managing smaller capital pools; Warren Buffett's shift toward moat investing was primarily driven by Berkshire's growing size rather than rejecting Graham's principles.

Legacy Returns

From 1965–2023, Warren Buffett's Berkshire portfolio achieved a remarkable per-share book value growth of 19.8%, significantly outperforming the S&P 500's 9.9%. The majority of these returns came during the "moat era," driven by major investments in companies like Coca-Cola, American Express (second investment), and Apple.

Graph suggestion: "Berkshire vs. S&P Total Return 1965–2023"—logarithmic scale with color-coded phases (pre-1972 net-net era and post-1972 moat era).

Investor Takeaways

Size Your Philosophy: Portfolios under $10m can effectively pursue net-nets; larger portfolios ($1bn+) must focus on moats or macro strategies.

Don't Confuse Price with Value: Low P/B ratios mean little without catalysts; high P/E ratios are acceptable with 30% ROIC reinvestment opportunities.

Time Horizon Arbitrage: Markets focus on quarterly results; moat investments compound over decades. Capitalize on this disconnect.

Qualitative ≠ Fuzzy: Warren Buffett's moat criteria—brand strength, network effects, cost advantages, regulatory protection—provide concrete evaluation tools, not just narrative elements.

Tax Deferral Is Alpha: Each year of holding adds implicit IRS-provided leverage through tax deferral.

Looking for the best Monopoly ETFs to invest in?

Check out Monopoly Hunters’ Top Monopoly ETF page on our website to learn about the different monopoly and oligopoly ETFs and what each one has to offer.

Looking for a way to track your investments (in one place)?

Visit Monopoly Hunters’ Free Resources page to download our Ultimate Investment Tracker. It’s free and lets you track all your investments in a single Google Sheet.

Bottom Line

Warren Buffett's journey from net-nets to moats wasn't a fundamental shift but rather a deeper application of value investing principles: buy below intrinsic worth.

The difference lay in valuation methodology—from liquidation value to discounted future cash flows protected by competitive advantages. Today's investors should choose strategies based on their capital base, temperament, and time horizon.

Net-nets can initiate wealth creation; moats can sustain long-term growth.

Remember Buffett's wisdom after decades of investing:

"Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre."

Let patience, not price movements, determine your winners.