How 21-Year-Old Warren Buffett Cold-Called CEOs On His 1951 Road-Trip

In late summer 1951, Warren Buffett packed his battered car outside New York, waved his wife Susie and infant daughter back to Omaha, and headed west alone.

In late summer 1951, Warren Buffett packed his battered car outside New York, waved his wife Susie and infant daughter back to Omaha, and headed west alone.

He was 21, a freshly minted Columbia grad with $9,800 of savings and an address book fattened by poring over Moody’s manuals. The plan was simple: drive, knock, listen, buy. Over ten days he zig-zagged through Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio, dropping in—unannounced—on coal pits, stove factories and a fading cooperage giant. “I didn’t have appointments; I would just drop in. I found that people always talked to me,” he later recalled.

That shoe-leather pilgrimage built the skeleton of Buffett’s first true portfolio—six positions, none larger than $4,000, all researched with nothing more than grit, curiosity and a willingness to cold-call company chairmen. Seventy-plus years later, it remains a masterclass in scuttlebutt investing at its purest.

The Map, the Miles and the Meetings

Buffett’s north-eastern loop looked like a salesman’s route:

Hazleton, PA – Jeddo-Highland Coal. Deep-value anthracite producer selling below liquidation.

Kalamazoo, MI – Kalamazoo Stove & Furnace. A bankruptcy scrap sale; Buffett inspected the building to judge residual asset worth.

Delaware, OH – Greif Bros. Cooperage. World’s largest wooden-barrel maker pivoting toward fibre drums; chairman John Dempsey welcomed the unshaven kid from Nebraska.

Each stop sharpened Buffett’s Ben-Graham toolkit: verify asset values in person, gauge managers’ candour, and test whether shrinking industries still printed cash. By trip’s end he had filled two notebooks, snapped roll after roll of Kodak film and—most important—had the conviction to buy big for his size.

The 1951 Road-Trip Portfolio

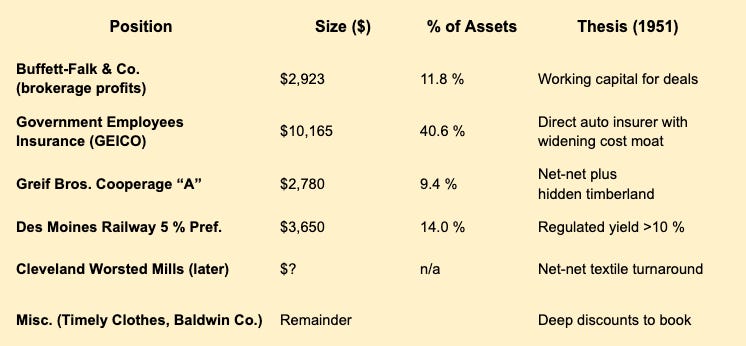

A few months later, year-end brokerage statements captured the results. Here are the six stocks, a $29,000 mini-fund, where four names consumed 80% of Buffet’s capital:

The headliner was GEICO, discovered the previous December when Buffett hopped a Saturday train to Washington, D.C., rapped on a locked office door and secured a five-hour tutorial from future CEO Lorimer Davidson. GEICO finished 1951 at more than half his net worth. The surprise No. 2 holding was Greif Bros. Why barrels in a plastics age? Buffett saw $39.60 of tangible book value selling for $18.25—“plenty of value in excess of market price,” he wrote Ben Graham two months later—and he’d tested it himself by talking to Greif foremen in the yard and the chairman in the office.

Cold-Calling as an Investing Edge

Buffett’s road-trip method wasn’t romantic wanderlust.

It solved three information problems of the 1950s:

Financial statements lagged. Annual reports arrived by mail months after fiscal year-end. Site visits yielded fresher data.

No sell-side coverage. Jeddo-Highland Coal or Kalamazoo Stove merited zero analyst notes; direct questions to managers filled the gap.

Behavioural calibration. Watching a CEO’s eyes when you mention share buybacks beats parsing prose.

Gardner notes that Buffett continued the habit for decades—sending associates to shareholder meetings, counting railcars in Kansas City, even checking restaurant tills to gauge American Express acceptance. The 1951 drive was simply version 1.0.

Case Study: Greif Bros. Cooperage

The barrel maker encapsulates why physical due diligence mattered. In 1951 Greif faced a secular decline: wooden slack barrels giving way to steel drums.

Buffett’s drop-in confirmed management had a transition plan—close mills, buy fibre-drum plants, redeploy sawmill timber—long before that narrative surfaced in print.

Financially, Greif’s net current asset value stood at $20.47 per share, and timber-backed tangible book at $39.60, versus an $18 stock. Buffett bought aggressively; by year-end it ranked second only to GEICO. The position didn’t become a 50-bagger—he sold after earning roughly 20 % annually—but the process cemented a pattern: find mispriced assets, cross-check on-site, size decisively, and invest wisely.

Why the Portfolio Worked

Concentration with conviction. At 40 % of assets, GEICO exceeded Graham’s recommended 10 % ceiling, but Buffett trusted the cost-advantaged model after interviewing Davidson.

Diversity of catalysts. GEICO was a compounder; Greif a balance-sheet bargain; Des Moines Railway a high-coupon preferred; Kalamazoo a liquidation. Each relied on different “ways to win,” lowering portfolio-level risk.

Micro-cap illiquidity edge. No mutual fund could touch Kalamazoo Stove’s scrap sale, but a $29 k portfolio could.

Scuttlebutt validation. Physical visits filtered frauds and clarified which cheap stocks were cheap for a reason.

Within three years Buffett chalked up 144.8 % in 1954 alone and laid the groundwork for the 29.5 % partnership CAGR that followed.

Looking for the best Monopoly ETFs to invest in?

Check out Monopoly Hunters’ Top Monopoly ETF page on our website to learn about the different monopoly and oligopoly ETFs and what each one has to offer.

Looking for a way to track your investments (in one place)?

Visit Monopoly Hunters’ Free Resources page to download our Ultimate Investment Tracker. It’s free and lets you track all your investments in a single Google Sheet.

Lessons for Today’s Investors

Primary research still scales. Regulatory filings now stream online, but insight often hides in site visits, trade-show chats or supplier calls—the modern echoes of Buffett’s barrel-yard banter.

Edge = effort × curiosity. Buffett wasn’t born with proprietary data; he earned it by knocking on factory doors. In an era of information parity, diligence depth is one of the few legitimate advantages.

Start small, think big. A 40 % bet on GEICO at 21 looked reckless; in hindsight it birthed Berkshire’s eventual $50 bn control purchase.

Beware desk-chair valuation. Buffett’s Greif memo to Graham stresses inventory accounting, shareholder buybacks and timber appraisals gleaned onsite—details screens can’t see.

Portfolio tables narrate risk. Buffett ended 1951 with just six names. The table (included above) is a humbling visual: excellence often comes from doing very little, very well.